Ghosts of Joh: An Interview with Kriv Stenders

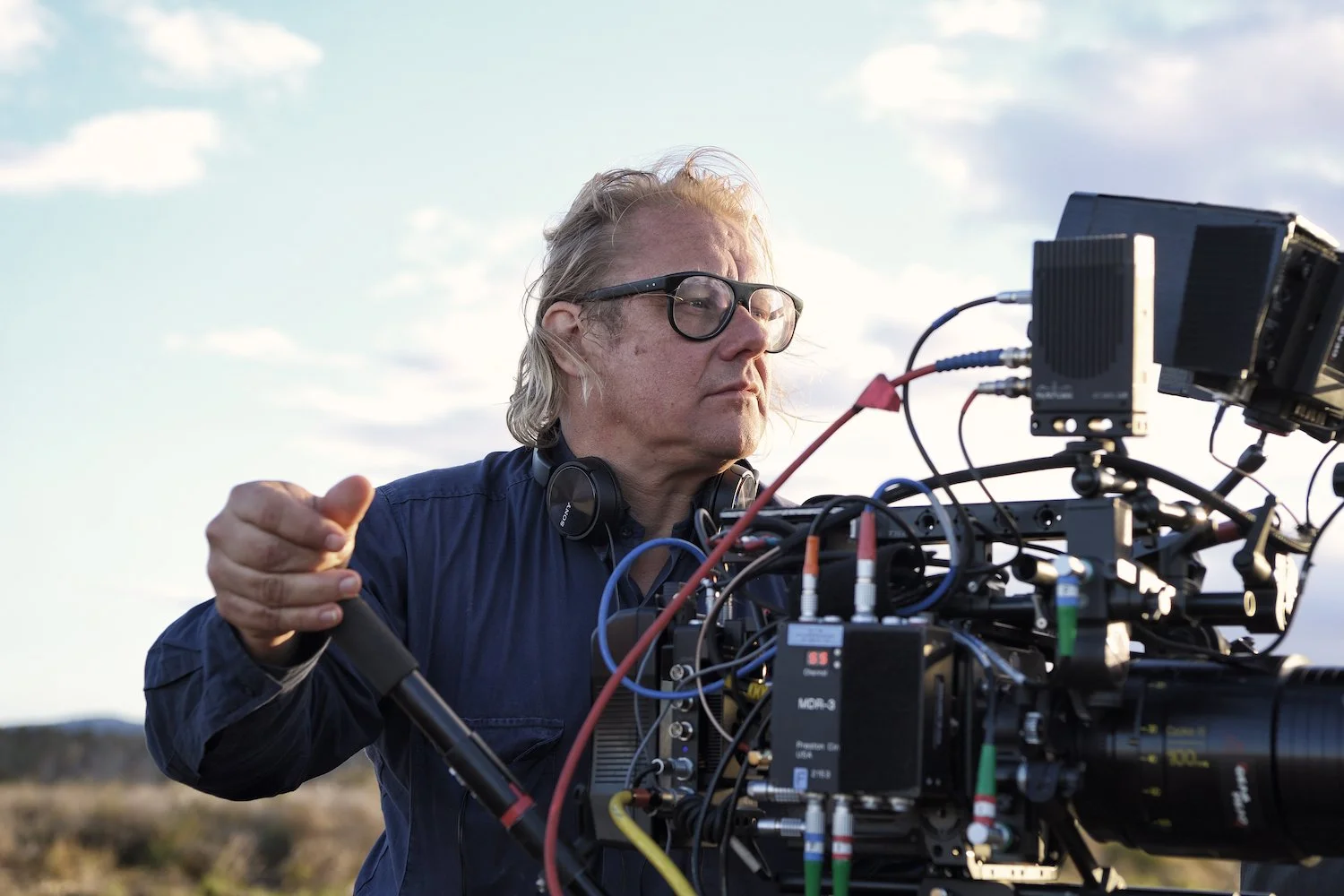

Photo: Kriv Stenders

Kriv Stenders is one of our finer active statesmen in regard to Australian cinema. The majority of his works are amorously Aussie creations that richly evoke the sunburnt country's culture, past, and personality. He has assessed our relationship with some of humanity's odious evils, namely war and racism. He has explored sunnier concepts, too, including beloved musicians and our true-blue manner of mateship. But despite an already vast filmography, comprising both fiction and non-fiction titles, Stenders' commitment to exploring the dimensions of down under has only widened, and his latest offering stakes a claim for his most controversial topic.

Said offering is Revealed - Joh: Last King of Queensland, a documentary that appraises the tempestuous career of Joh Bjelke-Petersen, the former long-serving Queensland premier. Although his name might not spring to mind as readily as it would for a prime minister, plenty would recognise his legacy. His leadership was defined by his championing of business and frequent disregard for civil liberties. This type of governance saw him pronounced a protector in equal measure to a despot. If that sounds familiar, the film repeatedly invokes the link this creates between him and the current U.S. Commander-in-Chief. But what Stenders additionally articulates is how easily absolute power invites corruption, and the extent to which it so badly previously festered in the Sunshine State.

Following its appearance at the Sydney Film Festival and its wider rollout on Stan, Stenders and I discussed the film on our respective lunch breaks. He told me about his personal ties to Joh, having a colleague inhabit him, and his hope that his audience is primarily younger generations. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This story contains mild spoilers for the film Revealed - Joh: Last King of Queensland.

CONNOR DALTON: What drew you to probing the life of Joh Bjelke-Petersen?

KRIV STENDERS: I grew up in Queensland. Throughout my childhood, teenage years, and early adulthood, I was under the shadow of Joh. He was ubiquitous. As a Queenslander, you couldn't escape him. He was a larger-than-life figure who affected so many of our lives in so many ways, both directly and indirectly. When we decided to look into the idea of making a film about Joh, it was really through the prism of now and what's happening with populism and authoritarian leadership around the world, specifically with Donald Trump. Due to men like him, the idea of the film had currency; it had value. So initially, it was a matter of connecting that with my past and my memories of Joh. Then, when I looked into the story and his life, I discovered it was Shakespearean. It was a huge, sprawling story about Queensland, about Australia, and so many themes — hubris, crime, corruption, power, grief, greed. It was full of delicious themes.

DALTON: Your recent collaborator, Richard Roxburgh, portrays an avatar of sorts for Joh in the film. Amid your talking heads and archive material, he appears on a stage throughout to bring Joh's speeches and writings to life. What was behind that choice?

STENDERS: I always feel that documentary is a great form because you can experiment, you can still be bold with it. The documentary language is constantly evolving, in terms of what a documentary is, what it can be, what it's been, and where it's going. And with every documentary I make, I really try to push the medium. I didn't want to make a dry, didactic, polemic documentary about the ills of Joh through just archive and talking heads. I wanted to give it life and give Joh life because there's archive on him, but it's always through news. It's always through the lens of political coverage, so it's very hard to get inside the man. Then it occurred to me, 'What if we went meta with it and got an actor on stage to basically perform Joh as if it was a one-man stage show?'

The one thing that really amazed me about the story when I started researching it was when Joh got ousted from office. I didn't realise he literally refused to leave. He was basically like Adolf Hitler, bunkered in his office. I thought, 'What a great conceit! What a great beginning to a film to have a character hold up in his office and then reflect back on his life.' That's when it all coalesced. From that point, I went, 'We'll do these monologues and have them continually woven into the unfolding narrative of the film, like a dialogue with the interviews.' It was one of those ideas, directorially, that gave me the tools to construct the film.

DALTON: When it comes to your interviewees, you have several politicians as part of your collective in David Littleproud, Bob Katter, and John Howard. How were they to work with?

STENDERS: It was very straightforward. I told them I was making a film about the life of Joh Bjelke-Petersen, I thought he was an important political and historical figure, and that they played a huge part in that story. For Littleproud, his father was in Joh's parliament, so there was a direct connection and lineage there. And I thought it was important that we showed both sides of the man. It wasn't just detractors. It was people who knew him, worked with him, and understood him. I think they understood that would be their purpose, so it was very straightforward. Bob Katter, particularly, was quite extraordinary. I talked to him for four hours. That man never stops; he's a very bright colour. But he was great because he was very candid and surprisingly articulate.

DALTON: Also present are Joh's now-adult children. Did it require much persuasion for them to join the fold?

STENDERS: They were very cautious. They'd been burnt before. But I was as transparent as possible with them at the beginning. I said, 'We are making this film about your father, about his life from soup to nuts, and I want to paint him as a human being. I don't want to paint him as a monster or a clown.' He was a politician, but he was also a father, a husband, and a grandfather. They are so directly related to him, and because he and [his wife] Flo have passed away, I really needed their voices and involvement in order to ground the film and to humanise Joh. I think it's important to look at these people as humans, as opposed to clowns, which is what I did when I was younger. That dismisses them and that gets them more power and makes them more dangerous, I think. To change power, you first need to understand it, and I wanted to go to the source and get a sense of who he was as a father.

DALTON: They don't really delve into their father's more transgressive actions.

STENDERS: Well, we covered everything. We interviewed so many people and we covered so much territory — his treatment of gays, his treatment of women and abortion. There was a litany of things that he did, but there came a point where we had that, and it was like one slap in the head after another, after another. How many times do we say that this guy was doing really quite reprehensible things and treating certain communities really badly? We tried not to generalise it, but give an overview, and say, 'Look, he obviously used his power incorrectly and abused it. There were students, gays, and women all affected by his rule.' But the film couldn't be just unrelenting and repetitive.

DALTON: You evince Joh's misdeeds, but he isn't the only one called out. You direct a searing condemnation at the Queensland Police for their rampant corruption during Joh's tenure.

STENDERS: Again, being a Queenslander, I grew up with those stories. You grew up knowing that the cops were corrupt. It was a given. There is a parallel story going on in the film, which is the story of police corruption in Queensland, especially from the '50s and '60s right through to the late '80s when it was finally kind of quashed. It happened in parallel with Joh's rise to power, so we couldn't ignore it. It was a story we had to unpack and tell in parallel with Joh's ascension, peak, and fall. That's why I got Matthew Condon on board the project as a co-writer because he's written the Three Crooked Kings trilogy of books, which looks at the story of [former police commissioner] Terry Lewis and the Rat Pack. It's hair-raising stuff; it could be a film or miniseries in itself. But I wanted to fuse it into the film because it is part of a broader cautionary tale. It's saying, 'This has happened, this is in our history, and this is what can happen again.'

DALTON: Like many others who held positions of great authority, Joh used his religion as a resource. Did that symbiosis interest you from a storytelling perspective?

STENDERS: When I first started talking about the story with Matthew Condon, he said, 'You've got to understand you can boil Joh down to two basic elements: land and faith. That's what Joh was constituted from. He was born on the land, worked on the land, driven by faith, and that engine propelled him all the way through his political career.' So it was vital in understanding him. I had to understand his religious leanings because that informed everything.

DALTON: There is a quote in the film's conclusion that stuck with me. David Margan states that Joh created history, but history has swiftly forgotten him. That may have been true, but change is already afoot. This film introduced me to Joh, and I'm sure that will be the case for many other viewers of my generation and beyond. How do you feel about that?

STENDERS: You've just made my day, Connor. To hear that makes the film so worthwhile. I have a 20-year-old son, and he saw the film; he was kind of gobsmacked by it. I think it's really important that new generations understand Australia and understand it through its history. So much of what Joh did and his legacy and his ghost are still around today in Australia. You can look at our attitudes and treatment of First Nations people. I mean, abortion wasn't legalised in Queensland until 2018. You've got to realise that, yeah, he was a man from the past and we're talking over 40 years ago, but he's still very relevant. As I said, it is a cautionary tale. It was made for younger generations to be made aware of the fact that we actually had a Trump. We had Trump here in the '70s and '80s, and we shouldn't forget that because he could easily return.

DALTON: In the wake of the film's release, I caught a post you uploaded to social media. You stated that this project nearly killed you. Considering you've been helming features for a little over thirty years, what made this story such a formidable challenge?

STENDERS: The documentaries are really tough. They are beasts. Unlike a drama, which is scripted and controlled, documentaries are wild. They're uncaged and mercurial because you don't know what the material and the story is until you start actually making it. Then there's the responsibility of telling the story properly, and I felt a huge responsibility because Joh was such a huge political and historical figure. I felt a huge responsibility to tell that story responsibly and comprehensively, so I was very hard on myself. When I commit to a project, I commit to it 1000%. Therefore, because of the density of the material, it did drag on me after a while. It was exhausting to keep the momentum and to find the story. Fiction filmmaking is like rock climbing with safety ropes and carabiners; documentary filmmaking is like free soloing. There's no safety net, and every step of the way, right until the film is finished, you're looking for that next crevice. You're hanging on for dear life, and there is a lot of blood, sweat, and tears. I'm still recovering from it, to be honest.

This article was originally published by The Curb